As the ETAS Journal is the original source of this post, I am deeply thankful for the amazing opportunity to have this article published in such a respectful periodical with so many respectful colleagues. This indeed led me to improve my writing skills as well as reflect more deeply on how to make my UI students to speak more naturally. Thank you very much!

Introduction:

Learning to speak a foreign language is much more complex than knowing its grammatical and semantic rules. It involves both command of certain skills and several different types of knowledge. Richards (2005, p. 204) states that learners must acquire the knowledge of how native speakers use the language in a context of structured interpersonal exchange, in which many factors interact.

Regarding oral communication, I believe learners need as much exposure as possible to the speaking skill to develop confidence. Through my experience I have noticed that it is a difficult area, especially for adult EFL learners. At the upper-intermediate level it is assumed that students have developed enough fluency and accuracy so as to communicate effectively. Usually at this level students are good at grammar, reading, and listening comprehension. In real life, however, it is difficult for them to communicate in L2 using the same natural speech they use in L1 because there are some ‘gaps’ in the teaching of the speaking skills which I intend to analyse later. Finally, of the four skills, speaking seems to be intuitively the most important.

According to Ur (2006, p. 120) people who know a language are referred to as ‘speakers’ of that language, as if speaking included all the kinds of knowing; and many, if not most, foreign language learners are primarily interested in learning to speak. This article will examine the factors affecting adult EFL oral communication, as well as components underlying mainly the use of discourse markers and speech acts. Analysis: According to Richards (2005, p. 204), it is difficult for EFL learners, especially adults, to speak the target language fluently and appropriately.

In order to provide effective guidance in developing competent English speakers, it is necessary to examine factors affecting adult learners’ oral communication. Owing to minimal exposure to the target language and contact with native speakers, adult EFL learners in general are relatively poor at spoken English, especially regarding fluency, control of idiomatic expressions, and understanding cultural pragmatics such as the use of speech acts, discourse markers and turn-taking, among others. Having said that, I assume EFL learners need explicit instructions in speaking, which, like any language skill, generally has to be learnt and practised. For Bygate (1987, p. 3), when speaking and listening abilities are focused on, we should put emphasis on teaching how to use language rather than knowing about language. He states that, in particular, learners need to develop skills in the management of interaction and also in the negotiation of meaning .

The management of interaction involves aspects such as knowing when and how to take the floor, when to introduce a topic or change the subject, how to invite someone else to speak, how to keep a conversation going, when and how to terminate the conversation and so on. In their mother tongue, students use these sub-skills and communicate with others unconsciously, whereas in their second language, they cannot always acquire these skills without practising. There is often a great deal of repetition and overlap between one speaker and another, and speakers frequently use fillers such as ‘well’, ‘oh’ and ‘uhuh’, making spoken language feel less conceptually dense than other types of languages, such as expository prose’.

According to Richards & Plat (1997, p. 343) a speech act is an utterance that serves a function in communication. It might contain just one word, as in "Sorry!" to perform an apology, or several words or sentences: "I’m sorry I forgot your birthday. Speech acts include real-life interactions and require not only knowledge of the language but also appropriate use of that language within a given culture. Here are some examples of speech acts we use or hear every day:

Greeting ( saying, "Hi, John!', for instance )

Apologising ( "sorry for that")

Warning ( "Watch out, the ground floor is slippery!")

McCarty (2004: p. 9) defines a discourse marker as a word or phrase that marks a boundary in a discourse, typically as part of a dialogue. They are usually polyfunctional elements and can be understood in two ways: firstly, as elements which serve to unite utterances (in this sense they are equivalent to connectives) and secondly, as elements which serve a variety of conversational purposes. It’s agreed that effective speakers are those who have mastered discourse competence. It means turn-taking in conversations, opening and closing a conversation, keeping a conversation going and repairing trouble spots in conversation. Discourse markers and speech acts are closely related because there is a bond between them. What I mean is that when a speech act is used in a conversation to express agreement, refusal, or any other function, it usually involves discourse markers to reinforce what the speech acts mean, as well as to make the conversation more authentic.

Problems

faced by learners

Speech acts are difficult to

perform in a second language because learners may not know the idiomatic

expressions or cultural norms in the second language or they may transfer their

first language rules and conventions into the second language, assuming that

such rules are universal. Something that works in English might not transfer in

meaning when translated into the second language. For example, the following

remark as uttered by a native English speaker could easily be misinterpreted by

a native Chinese hearer:

Sarah: "I couldn't agree with you

more."

Cheng: "Hmmm…."(Thinking:

"She couldn't agree with me? I thought she liked my idea!")

According to

my research some EFL learners may unintentionally come across as abrupt or

brusque in social interactions in English because of a lack of expertise with

linguistic devices such as discourse markers.

Being a teacher in monolingual groups of students, I have notices that they have few opportunities to practise sub-skills associated with the spoken language that are not naturally practised in the classroom. Students learn basic or non-authentic vocabulary at the early stages. Consequently, at the upper intermediate stage they need more contact with how discourse markers are used when speaking and to be shown the importance of using them correctly and, with practice, as authentically as possible.

Helping learners:

Helping learners:

Thornbury (2006, p. 41) states that there are things learners can’t easily do because they lack certain skills. On the other hand, there are things learners do not know how to do, such as what to say to signal a change of topic. I decided to use awareness-raising activities, since they allow the possibility of learners’ discovering, not to mention that this kind of activities involve attention, noticing and understanding.

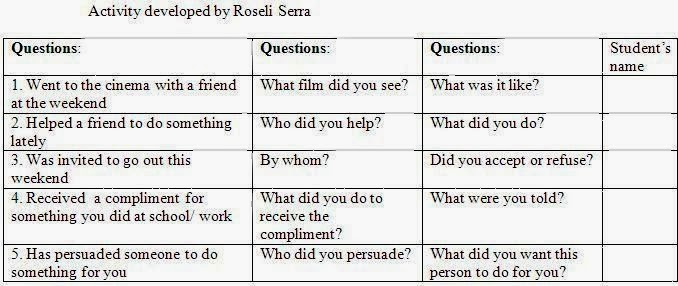

As a lead-in I used a “find someone who” activity which aims to introduce the topic of making invitations and suggestions, to expand conversation in the target language and raises students’ awareness of the target language while using students’ common sense as background to support it.

Slide developed by Roseli Serra @SerraRoseli

To raise learners’ awareness of features of spoken language I used an activity adapted from THORNBURY, Scott, How To Teach Speaking (2006, p. 51). It aims to make students able to recognise a number of speech acts, and raise their interest in particular features of the spoken language using the language point.

Asking learners to categorize speech acts is another way of raising awareness

as to their meaning and use. In this activity students listen to some

dialogues, match them to pictures and categorise a variety of speech acts

relating to the macro-function of ‘getting people to do things’. (Adapted from

CUNNINGHAN, Sarah, Cutting Edge

Advanced (2006, p. 35)

As stated before, it is useful to encourage students to recognise

that spoken language can be untidy and include elements like false starts and

fillers. This can be done by looking at

transcripts of natural language. I have handed out the transcript of the above dialogues aiming to have students identifying the discourse

markers and get them to notice and reflect about the language in use and focus

on the spontaneous spoken language leading them to use those features in the

next activities.

After showing the students a PowerPoint presentation containing some

discourse markers from the text ( As in the image above) , and also some speech acts from the previous

activities, I used an activity proposed in CLAIRE, Antonia & WILSON, JJ, Language to Go Upper-Intermediate – students’ Book (2002, p.

87) as a role playing/simulation. It encourages thinking and creativity, lets

students develop and practice new language and behavioural skills in a

relatively nonthreatening setting, and can create the motivation and

involvement necessary for learning to occur. At this stage of the lesson the

students will be aware of discourse markers.

So it is time to give them opportunities to produce the target language.

As most spoken language is, by its very nature, spontaneous, some

aspects seem very difficult to teach at first sight. On the other hand, some

aspects are very teachable. We can demonstrate typical exchanges, such as those

used for offers or requests. In doing so we can focus on interactive markers

like right, okay, fine and so

on. According to Wills (2005, p. 198),

all of these elements have an identifiable value which can, in principle, be

made available to students.

I think this work is worthwhile because we can make students aware of the nature and

characteristics of the spoken language. Furthermore, we can give them

opportunities to analyse and to produce spontaneous language. Most important of

all, we need to recognise the dynamic nature of spoken language. “Language is

the way it is because of the purpose it fulfils”. (See Wills 2005, p. 198)

I also concluded that one thing is certain: if we are to illustrate

grammar of spoken English, we need samples of genuine spoken interaction. However,

I would like to say that this too create problems. As we know, spoken language

can be untidy, full of false starts and instances of speakers talking over

another. This can make it difficult to process.

Spontaneous spoken language is often delivered rapidly, unlike the

carefully modulated language we hear in most language courses. In the real world, the processing of spoken

language often depends on shared knowledge and is consequently highly

inexplicit.

With this in mind, the teacher must then set achievable goals that

are applicable and suitable for the communication needs of the student. The

student must also become part of the learning process, actively involved in

their own learning. With the teacher acting as a 'speech coach', rather than as

mere checker of students’ performance, the feedback given to the student can

encourage learners to improve their spoken skills. If these criteria are met, all students,

within their learner-unique goals, can be expected to do well in learning how

to speak English spontaneously.

Enjoy your teaching!

Bibliography:

Brown,

G., & Yule, G. (1993). Teaching the spoken language: an approach based

on the analysis of conversational English. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Bygate,

M. (1987). Speaking. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clare, A., & Wilson, J. J.

(2002). Language to go: upper intermediate. Harlow: Longman.

Cunningham, S., & Moor, P.

(2003). Cutting edge: advanced,. Harlow: Longman.

McCarthy,

M. (1991). Discourse analysis for language teachers. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Nunan,

D. (1989). Designing tasks for the communicative classroom. Cambridge

[England: Cambridge University Press.

Richards,

J. C., Platt, J. T., & Weber, H. (1985). Longman dictionary of applied

linguistics. Harlow, Essex, England: Longman.

Richards,

J. C. (1990). The language teaching matrix. Cambridge [England:

Cambridge University Press.

Richards,

J. C., & Renandya, W. A. (2002). Methodology in language teaching: an

anthology of current practice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Scarcella,

R. C., & Oxford, R. L. (1992). The Tapestry of language learning: the

individual in the communicative classroom. Boston, Mass.: Heinle &

Heinle.

Scrivener, J. (2011). Learning

Teaching (3., neue Aufl. ed.). Ismaning: Hueber Verlag.

Thornbury, S. (2005). How to

teach speaking. Harlow, England: Longman.

Ur,

P., & Ur, P. (2012). A course in English language teaching (2nd

ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Willis,

D. (2003). Rules, patterns and words: grammar and lexis in English language

teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

14 comments:

Best article ever!

Excellent ever!!!!!!!!!!!!!1

Thanks so much Roseli for sharing it. I found the article very useful and just what I needed. :)

Great!! (y)

Dear Stephanie.

Thank you so much for your encouraging words! I'm so happy you liked my article.

Feel free to get in touch!

Cheers.

Roseli

Thank you Eli!

I feel honoured you like it!

Cheers!

Roseli

Dear Rose Bard,

Your words mean a lot to me!

Thank you so much for reading and enjoying it!

Feel hugged and blessed!

Cheers!

Roseli

Thank you Anonymous!

Whoever you are, I fell happy you enjoyed mu post!

Cheers!

Roseli

Great yar & thanks

It is a wonderful and very expressive article. thanks so much!

Dear Mesbah and Anonymous ,

Thank you very much for your encouraging words. I fell very honoured you've read and enjoyed my post/article!

Cheers!

Roseli

Interesting write-up! Writing is an art form that reaches a multitude of people from all walks of life, different cultures, and age group. As a writer, it is not about what you want.examples of slang words

Great piece of writing!

Learning to speak a foreign language is much more complex than knowing its grammatical and semantic rules. It involves both command of certain skills and several different types of knowledge.

Vocabulary is needed whether its's job or a student learning afor his exam. www.vocabmonk.com is one of the sites has helped to build my vocabulary.

Hi, Fazi and Vocabulary Monk, I'm so glad you like it.

Thank you ever so much for your comments. Please, feel free to use the activities, adapt them and share.

All the best,

Roseli

Post a Comment